Black History and Heritage Outreach

The Black History Heritage Outreach Ministry is an evangelistic approach seeking to share our culture and ideas with the entire Christian Church community. We share planned spiritual and educational programs each year educating the school and church community about African American Saints and the contributions they have made enriching our the Black Catholic faith.

We want to make known the significant contributions that African American people have made over the years by being humble servants of God. There is richness in our Black experience that is expressed through our Catholic faith.

Black History Month is always celebrated at Holy Family with special guest speakers, celebrants and the celebration of the Mass with visiting Gospel Choirs and a potluck community supper.

Members are encouraged to share their spiritual gifts and talents as well as shine a light with the church community. We sponsor annually a Martin Luther King mass, spring bake sale, and support a food booth at Holy Family Fun Family International festival.

Black spiritually is a gift of Joy; this joy is a sign of our faith! Our theme song is: “We’ve Come this Far By Faith”.

New members are always welcome. For more information, please contact co-chairs, Beverly Carroll at [email protected], 703-929-4465 or Pat Brooks at [email protected], 703-590-1859.

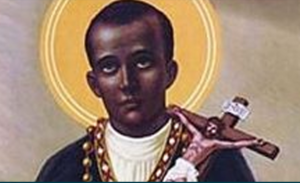

'Racism to Sainthood’ Venerable Augustus Tolton

“I shall work and pull at it as long as God gives me life for I am beginning to see that I have power and principalities to resist anywhere and everywhere I go.”

Fr. Tolton was a former slave and the first African American diocesan priest in the United States. He founded the first African American Catholic parish in Chicago. Prayer cards and pamphlets will be available in the Vestibule.

Saints

St Katharine Drexel used her personal fortune to fund schools for Native Americans and African Americans. She was canonized in 2000.

In 1891, Saint Katharine Drexel left her life as an heiress behind when she became a nun. She subsequently founded the order of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament and used her fortune to create new schools for Native Americans and African Americans across the United States. She died in 1955 at age 96 and was canonized as a Catholic saint in 2000.

Drexel was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 26, 1858. Her father, Francis Anthony Drexel, was a business partner of financier J.P. Morgan. Her mother, Hannah Jane (née Langstroth) Drexel, died a month after Drexel’s birth; in 1860, her father was married again to Emma Bouvier. In addition to their great wealth, her parents were known for their philanthropic endeavors.

Drexel was raised as a young heiress in Philadelphia and was educated at home. However, having traveled throughout the United States, she was aware of the difficult circumstances faced by Native Americans and African Americans across the country. Drexel – who lost her stepmother in 1883 and her father in 1885 – wanted to use her inherited wealth to help these groups.

Drexel supported several schools, including one that was located on a reservation in South Dakota. During a trip to Europe in 1887, she met Pope Leo XIII and asked him to recommend a religious order that could send missionaries to the institutions she was funding. He suggested that Drexel might undertake the missionary work herself.

St. Martin de Porres was born in Lima, Peru on December 9, 1579. Martin was the illegitimate son to a Spanish gentleman and a freed slave from Panama, of African or possibly Native American descent. At a young age, Martin’s father abandoned him, his mother, and his younger sister, leaving Martin to grow up in deep poverty. After spending just two years in primary school, Martin was placed with a barber/surgeon where he would learn to cut hair and the medical arts.

As Martin grew older, he experienced a great deal of ridicule for being of mixed-race. In Peru, by law, all descendants of African or Indians were not allowed to become full members of religious orders. Martin, who spent long hours in prayer, found his only way into the community he longed for was to ask the Dominicans of Holy Rosary Priory in Lima to accept him as a volunteer who performed the most menial tasks in the monastery. In return, he would be allowed to wear the habit and live within the religious community. When Martin was 15, he asked for admission into the Dominican Convent of the Rosary in Lima and was received as a servant boy and eventually was moved up to the church officer in charge of distributing money to deserving poor.

During his time in the Convent, Martin took on his old trades of barbering and healing. He also worked in the kitchen, did laundry and cleaned. After eight more years with the Holy Rosary, Martin was granted the privilege to take his vows as a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic by the prior Juan de Lorenzana who decided to disregard the law restricting Martin based on race.

However, not all of the members in the Holy Rosary were as open-minded as Lorenzana; Martin was called horrible names and mocked for being illegitimate and descending from slaves.

Martin grew to become a Dominican lay brother in 1603 at the age of 24. Ten years later, after he had been presented with the religious habit of a lay brother, Martin was assigned to the infirmary where he would remain in charge until his death. He became known for encompassing the virtues need to carefully and patiently care for the sick, even in the most difficult situations.

Martin was praised for his unconditional care of all people, regardless of race or wealth. He took care of everyone from the Spanish nobles to the African slaves. Martin didn’t care if the person was diseased or dirty, he would welcome them into his own home.

Martin’s life reflected his great love for God and all of God’s gifts. It is said he had many extraordinary abilities, including aerial flights, bilocation, instant cures, miraculous knowledge, spiritual knowledge and an excellent relationship with animals. Martin also founded an orphanage for abandoned children and slaves and is known for raising dowry for young girls in short amounts of time.

During an epidemic in Lima, many of the friars in the Convent of the Rosary became very ill. Locked away in a distant section of the convent, they were kept away from the professed. However, on more than one occasion, Martin passed through the locked doors to care for the sick. However, he became disciplined for not following the rules of the Convent, but after replying, “Forgive my error, and please instruct me, for I did not know that the precept of obedience took precedence over that of charity,” he was given full liberty to follow his heart in mercy.

St. Peter Claver, SJ, was a member of the Society of Jesus and is the patron of African missions and of interracial justice, due to his work with slaves in Colombia.

Peter Claver was born to a prosperous family in Verdu, Spain, and earned his first degree in Barcelona. He entered the Jesuits in 1601. When he was in Majorca studying philosophy, Claver was encouraged by Alphonsus Rodriguez, the saintly doorkeeper of the college, to go to the missions in America. Claver listened, and in 1610 he landed in Cartagena, Colombia. After completing his studies in Bogotá, Peter was ordained in Cartagena in 1616.

Cartagena was one of two ports where slaves from Africa arrived to be sold in South America. Between the years 1616 and 1650, Peter Claver worked daily to minister to the needs of the 10,000 slaves who arrived each year.

When a ship arrived, Peter first begged for fruits, biscuits, or sweets to bring to the slaves. He then went on board with translators to bring his gifts as well as his skills as a doctor and teacher. Claver entered the holds of the ships and would not leave until every person received a measure of care. Peter gave short instruction in the Catholic faith and baptized as many as he could. In this way he could prevail on the slave owners to give humane treatment to fellow Christians. Peter Claver baptized more than 300,000 slaves by 1651, when he was sickened by the plague.

In the last years of his life Peter was too ill to leave his room. The ex-slave who was hired to care for him treated him cruelly, not feeding him many days, and never bathing him. Claver never complained. He was convinced that he deserved this treatment.

In 1654 Peter was anointed with the oil of the Sacrament of the Sick. When Cartagenians heard the news, they crowded into his room to see him for the last time. They treated Peter Claver’s room as a shrine, and stripped it of everything but his bedclothes for mementos. Claver died September 7, 1654.

St. Peter Claver was canonized in 1888. His memorial is celebrated on September 9.

Quote: “We must speak to them with our hands before we speak to them with our lips.”

Martin was great friends with both St. Juan Macías, a fellow Dominican lay brother, and St. Rose of Lima, a lay Dominican.

In January of 1639, when Martin was 60-years-old, he became very ill with chills, fevers and tremors causing him agonizing pain. He would experience almost a year full of illness until he passed away on November 3, 1639.

On The Road To Be Saints

Venerable

Venerable Pierre Toussaint (born Pierre; 27 June 1766 – June 30, 1853) was a Haitian American hairdresser, philanthropist, and former slave brought to New York City by his owners in 1787. Freed in 1807 after the death of his mistress, Pierre took the surname of “Toussaint” in honor of the hero of the Haitian Revolution. In 1996, he was declared “Venerable” by Pope John Paul II.

After his marriage in 1811 to Juliette Noel, Toussaint and his wife opened their home as an orphanage, employment bureau, and a refuge for travelers. He also contributed funds and helped raise money to build Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street. He was considered “one of the leading black New Yorkers of his day.” His ghostwritten memoir, Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, was published in 1854.

Toussaint is the first layperson to be buried in the crypt below the main altar of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, generally reserved for bishops of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York.

Pierre was born into slavery on June 28, 1766, in what is now known as Haiti. He was the son of Ursule, and resided on the Artibonite plantation owned by the Bérard family. The plantation was located on the Artibonite River near Saint-Marc on the colony’s west coast. His father’s name is not known. He was known to have a sister Rosalie. His maternal grandmother, Zenobe Julien, was also a slave and was later freed by the Bérards for her family service. His maternal great-grandmother, Tonette, had been born in Africa, where she was sold into slavery and brought to Saint-Domingue. He was raised as a Catholic.

Pierre was educated as a child by the Bérard family’s tutors and was trained as a house slave. The senior Bérards returned to France, taking Zenobe Julien with them, and their son Jean Bérard took over the plantation. As the tensions rose, which would lead to Haitian slaves and free people of color rising in rebellion, in 1787 Bérard and his second wife left the island for New York City, taking five of their slaves with them, including Pierre and Rosalie.

Upon their arrival in New York, Bérard had Pierre and Sir Joint apprenticed to one of New York’s leading hairdressers. The master returned to Saint-Domingue to see to his property. After Jean Bérard died in St. Domingue of pleurisy, Pierre, who was becoming increasingly successful as a hairdresser in New York, voluntarily took on the support of Madame Bérard. His master had allowed him to keep much of his earnings from being hired out. (Pierre’s kindness to his mistress was noted by one of her friends, Philip Jeremiah Schuyler’s second wife Mary Schuyler, whose notes were a source for the 1854 memoir of Toussaint.) Madame Bérard eventually remarried, to Monsieur Nicolas, also from Saint-Domingue. On her deathbed, she made her husband promise to free Pierre from slavery.

As a very popular hairdresser among New York society’s upper echelon, Toussaint earned a good living. He saved his money and paid for his sister Rosalie’s freedom. They both still lived in what was then the Nicolas house. He was freed in 1807.

Catherine (“Kitty”) Church Cruger, two years older than Toussaint, would become one of his key clients and friends. She was the daughter of John Barker Church (who would give the pistols to Hamilton for the duel in Weehawken) and Angelica Schuyler, the muse and confidante of Hamilton and Jefferson.

Due to connections among the French emigrant community in New York, Toussaint met people who knew the Bérards in Paris. He began a correspondence with them that lasted for some decades, particularly with Aurora Bérard, his godmother. The Bérards had lost their fortune in the French Revolution, during which Aurora’s father died in prison and her mother soon after. Her other siblings had married in France. Toussaint also corresponded with friends in Haiti; his collected correspondence filled 15 bound volumes, as part of the documentation submitted by the Archdiocese of New York to the Holy See to support canonization.

On August 5, 1811, Toussaint married Juliette Noel, a slave 20 years his junior, after purchasing her freedom. For four years, they continued to board at the Nicolas house. They adopted Euphemia, the daughter of his late sister Rosalie who had died of tuberculosis, raising the girl as their own. They provided for her education and music classes. In 1815, Nicolas and his wife moved to the American South. Together, the Toussaints began a career of charity among the poor of New York City, often taking baked goods to the children of the Orphan Asylum and donating money to its operations.

Toussaint attended daily Mass for 66 years at St. Peter’s in New York. He owned a house on Franklin Street, where the Toussaints sheltered orphans and fostered numerous boys in succession. Toussaint supported them in getting an education and learning a trade; he sometimes helped them get their first jobs through his connections in the city.

They also organized a credit bureau, an employment agency, and a refuge for priests and needy travelers. Many Haitian refugees went to New York, and because Toussaint spoke both French and English, he frequently helped the new immigrants. He often arranged sales of goods so they could raise money to live on. He was “renowned for crossing barricades to nurse quarantined cholera patients” during an epidemic in New York.

Toussaint also helped raise money to build a new Roman Catholic church in New York, which became Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street. He was a benefactor of the first New York City Catholic school for Black children at St. Vincent de Paul on Canal Street.

As Toussaint aged, he continued his charity. At his death, his papers included records of his many charitable gifts to Catholic and other institutions; friends and acquaintances lauded his character. He was “one of the leading black New Yorkers of his day,” but his story became lost to history.

Euphemia died before her adoptive parents, of tuberculosis, like her mother. Juliette died on May 14, 1851. Two years later, Pierre Toussaint died on June 30, 1853, at the age of 87. He was buried alongside his wife and Euphemia in the cemetery of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral on Mott Street.

Venerable Henriette Delille, 1812 – 1862 “SERVANT OF SLAVES” Born in 1812, Henriette Delille was a real life person like you and me. She was born a free woman of color and lived her life in New Orleans, Louisiana. Henriette was surrounded by family and friends.

Among Henriette’s relatives was her great, great grandmother who was a slave from West Africa. Her mother and the other women in her family formed liaisons or serial monogamous relationships with white men. This means colored women “in concubinage” with wealthy white men. In recent findings, in funeral records, Henriette may have given birth to two sons who died before the age of three. She had one sister and two brothers, one of whom died in infancy. Descendants have been found and are in touch with the Sisters.

When Henriette was 24 years old, she underwent a religious experience. This religious experience is expressed in a brief declaration of faith and love. On the flyleaf of a book centered on the Eucharist, is a profession of love, in her own handwriting. Written in French: “Je crois en Dieu. J’espère en Dieu. J’aime. Je v[eux] vivre et mourir pour Dieu.”

In 1836 Henriette drew up the rules and regulations for devout Christian women, which would eventually become the Society of the Holy Family. The group was founded for the purpose of nursing the sick, caring for the poor, and instructing the ignorant.

1842 is the date for the founding of the Sisters of the Holy Family for the same purposes. Henriette was assisted by her friends, Juliette Gaudin and Josephine Charles. Records show that these women served as godmothers to many: slaves, free, children, and adults. They also witnessed many marriages.

With a three pronged program and a set of carefully drawn up rules, they expressed their apostolic intentions through caring for the sick, helping the poor, and instructing the ignorant of their people, free and enslaved, children and adults, in the name of Jesus Christ and the Church.

They took into their home elderly women who needed more than visitation, and thereby opened America’s first Catholic home for the elderly of its kind, as recorded in the National Register. Noteworthy are the heroic efforts of the early Sisters who cared for the sick and the dying during the yellow fever epidemics that struck New Orleans in 1853 and 1897.

In the eyes of the world Henriette may not have accomplished much, but her obituary and the Catholic Church tell us otherwise. ” . . . (Henriette) devoted herself untiringly for many years, without reserve, to the religious instruction of the people of New Orleans, principally of slaves. . . .” The last line of her obituary reads, “. . . for the love of Jesus Christ she had become the humble and devout servant of the slaves.”

Because she lived such a holy, prayerful, and virtuous life, we, the Sisters of the Holy Family, wanted to present her to the world as a model of a true Christian. Therefore, we asked, from the Catholic Church, permission to begin a canonization process. Through the efforts of the late Archbishop Philip Hannan, this request was granted by Blessed John Paul II in 1988. The Church then declared her “Servant of God.”

The process to sainthood has four phases: servant of God, venerable, blessed, and saint. Two of the phases, servant of God and venerable, are complete. Venerable was decreed by Pope Benedict XVI March 27, 2010.

Venerable Henriette Delille is the first United States native born African American whose cause for canonization has been officially opened by the Catholic Church. What remains for the process to be complete is the validation of an alleged miracle which is now being processed. If all goes well and Pope Francis issues the decree of the alleged miracle’s authenticity, then Henriette will be proclaimed blessed.

What follows is a glorious ceremony and celebration in New Orleans. A second miracle would be needed for sainthood.

Venerable Henriette Delille lived her prayer: “I believe in God. I hope in God. I love. I want to live and die for God.”

Venerable Fr. Augustus Tolton, who conquered almost insurmountable odds and is now regarded as the very first black Roman Catholic priest in the United States.

Fr. Tolton was born in 1854 in Missouri into a black Catholic slave family, shortly after Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery and two years after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published.

Augustus moved with his mother and two siblings to Quincy, Illinois in 1862 with the aid of a handful of Union soldiers. They joined a Catholic church whose congregation was largely constituted by German immigrants, and at the age of 9, Augustus began working in a tobacco factory.

Encouraged by his mother to pursue an education, he met with resistance from many area Catholic schools because parish and staff were threatened and harassed by his presence. Augustus also discussed the possibility of entering the priesthood, yet no American seminary would admit a black student.

In 1868, Augustus succeeded in enrolling in St. Peter School in Quincy, IL. He was confirmed at St. Peter Church at age 16 and graduated from St. Peter School at age 18.

Tolton was then tutored privately by local priests until Quincy University (then St. Francis Solanus College) admitted him in 1878 as a special student. He departed for Rome on February 15, 1880, to enter the seminary there. He expected to become a missionary priest in Africa.

Tolton was ordained at St. John Lateran Basilica in Rome on April 24, 1886 and told he would return as a missionary to his home country of the United States in Quincy Illinois! He returned to his hometown to become pastor of St. Joseph Church in Quincy, IL, a mainly black church.

Tolton became such a popular preacher that he attracted some members of local white – mostly German or Irish – congregations. He therefore also faced discrimination from other local priests, who resented what they perceived as competition.

The St. Augustine Society, an African American Catholic charitable organization, contacted Tolton about moving to Chicago to help its members found a congregation.

In late 1889, Rome granted him a transfer to Chicago, where he not only became the city’s first African American priest but also was granted jurisdiction by the archbishop over all of Chicago’s black Catholics. At the beginning he ministered to a black congregation in the basement of an old church.

Through the combined efforts of Tolton and the St. Augustine Society, as well as a private gift, enough money was raised to build most of the structure for a church building, and in January 1894, Tolton held Mass in the new St. Monica Church on Chicago’s South Side, built by people of African American descent for that same community to worship. Tolton was its first pastor.

He soon developed a national reputation as a minister and as a public speaker, yet he devoted the majority of the remainder of his life to his congregants, most of whom lived in poverty, and to the completion of St. Monica Church.

He died shortly after succumbing to heat stroke at the age of 43.

Although slavery ended legally after the American Civil War, severe racial prejudice remained dominant in American life for many decades, and the Catholic Church was not immune to this evil. Participation of blacks in ordinary political, economic, social, and even religious life was hampered and curtailed at every turn.

Father Tolton lived courageously in the midst of this prejudice with the help of some Catholic priests, religious sisters, and laity. Tolton’s story is one of carving out one’s humanity as a man and as a priest in an atmosphere of racial volatility. His was a fundamental and pervasive struggle to be recognized, welcomed, and accepted.

Bishop Joseph Perry, Auxiliary Bishop of Chicago, wrote:

Fr. Tolton is on the road to canonization as a saint. His cause was opened in early 2012 when he was named Servant of God, and he is currently awaiting beatification.

O God, we give you thanks for your servant and priest, Father Augustus Tolton, who labored among us in times of contradiction, times that were both beautiful and paradoxical. His ministry helped lay the foundation for a truly Catholic gathering in faith in our time.

We stand in the shadow of his ministry. May his life continue to inspire us and imbue us with that confidence and hope that will forge a new evangelization for the Church we love.

Servants of God

Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange was born in 1784 in Haiti, an island in the Caribbean. Her parents fled Haiti during a revolution and went to Cuba, where Lange received her education. She came to Baltimore in 1813 and settled in Fells Point. Baltimore had a large population of French-speaking Caribbean Catholics. Lange, a well-educated free black woman in a slave-holding state, also had money from her merchant father. She saw a need in educating children of Caribbean immigrants and slaves, a practice which was illegal at that time.

Lange used her money and set up a school in her home with her friend, Marie Magdaleine Balas. They offered a free education, but after 10 years finances became a problem. Rev. James Hector Joubert, a Sulpician with the backing of the Archbishop of Baltimore Monsignor James Whitfield, came to the rescue. Joubert presented Lange with a challenge to found a religious congregation for the education of black children. Joubert would provide direction, solicit financial assistance and encourage other women of color to become members of the first order of African American nuns in the history of the Catholic Church. On July 2, 1829, Lange and three other women pronounced promises of obedience to the Archbishop and the chosen superior.

Lange, the founder and first superior of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, took the name Mary. The Oblate sisters educated youths and provided homes for orphans. They nursed the sick and dying and sheltered the elderly.

Mother Mary Lange’s deep faith enabled her to persevere against all odds. Lange was a woman of vision and selfless commitment. She personally took action to meet the social, religious and educational needs of poor women and children. Her influence is still felt today around the world where the Oblate Sisters of Providence minister to young and old alike. Their ministry is particularly felt in Baltimore at the St. Frances Academy.

Mother Mary Lange died Feb. 3, 1882. Cardinal William H. Keeler and the Oblate Sisters have campaigned for her canonization and the Vatican has this under study.

Julia Greeley, O.F.S. (c. 1833-48 – 7 June 1918), was an African American philanthropist and Catholic convert. An enslaved woman later freed by the US government, she is known as Denver’s “Angel of Charity” because of her aid to countless families in poverty. Her cause for canonization was opened in 2014.

Greeley was born into slavery in Hannibal, Missouri. At the age of five, her right eye was injured by a slave master as he was whipping her mother. This disfigurement remained with Greeley the rest of her life. She became referred to as “one-eyed Julia”.

In 1865, Greeley was freed during the Civil War under the Emancipation Proclamation.

She then moved to Denver and in 1879 became a cook and nanny to Julia Pratte Dickerson of St. Louis, a widow who would later marry William Gilpin-who had been appointed by President Abraham Lincoln as the first territorial Governor of Colorado.

Greeley was baptized into the Catholic Church on June 26, 1880, at Sacred Heart Church in Denver, and became especially devoted to the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the Holy Eucharist, receiving Holy Communion daily. Despite secretly suffering from painful arthritis, she tirelessly walked the city streets distributing literature from the Sacred Heart League to Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

She became known for her charitable works, pulling a red wagon through the streets of Denver in the dark to bring food, coal, clothing, and groceries to needy families. She made her rounds after dark so as not to embarrass white families ashamed to accept charity from a poor, black woman.

In 1901, Greeley joined the Secular Franciscans and remained an active member for the rest of her life. She died on June 7, 1918.

In January 2014, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Denver officially opened an investigation for her sainthood.

Greeley is one of the four people that U.S. bishops voted to allow to be investigated for possible sainthood at their fall meeting that year. She joins four other African Americans placed into consideration in recent years. She was also the first person to be interred in the Denver cathedral since it opened in 1912.

As of May 2021, her official inquiry has been accepted and validated by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, and a positio summarizing her life is now being written.

Greeley spent the majority of her time helping others and completing church duties. Years later when the Gilpins died, Greeley began to do labor work for a number of wealthy white families. With this money she made, she decided to give it all away to people who needed it. She went all around Denver, supplying poor families with needs like clothes and food. One of her major acts of kindness was when she donated her own burial plot for an African American man who died. He was going to be laid into a Pauper’s grave, but Greeley would not let that happen. After this, many people began to call her the “colored angel of charity” because of her kindness. Because of all her dedication to families in poverty, she was officially named “Denver’s Angel of Charity”.

Servant of God Bertha Elizabeth Bowman, Born December 29, 1937, in Yazoo City, Mississippi, Thea was reared as a Protestant until at age nine when she asked her parents if she could become a Catholic.

Servant of God Bertha Elizabeth Bowman, Born December 29, 1937, in Yazoo City, Mississippi, Thea was reared as a Protestant until at age nine when she asked her parents if she could become a Catholic.

Gifted with a brilliant mind, beautiful voice and a dynamic personality, Sister Thea shared the message of God’s love through a teaching career. After 16 years of teaching, at the elementary, secondary and university level, the bishop of Jackson, Mississippi, invited her to become the consultant for intercultural awareness.

In her role as consultant Sister Thea, an African American, gave presentations across the country; lively gatherings that combined singing, gospel preaching, prayer and storytelling. Her programs were directed to break down racial and cultural barriers. She encouraged people to communicate with one another so that they could understand other cultures and races.

A self-proclaimed, “old folks’ child,” Bowman, was the only child born to middle-aged parents, Dr. Theon Bowman, a physician and Mary Esther Bowman, a teacher. At birth she was given the name Bertha Elizabeth Bowman. As a child she converted to Catholicism through the inspiration of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity who were her teachers and pastors at Holy Child Jesus Church and School in Canton.

At an early age, Thea was exposed to the richness of her African American culture and spirituality, most especially the history, stories, songs, prayers, customs and traditions. At the age of fifteen, she told her parents and friends she wanted to join the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and left the familiar Mississippi terrain to venture to the unfamiliar town of LaCrosse, Wisconsin where she would be the only African American member of her religious community. At her religious profession, she was given the name, “Sister Mary Thea” in honor of the Blessed Mother and her father, Theon. Her name in religious life, Thea, literally means “God.” She was trained to become a teacher. She taught at all grade levels, eventually earning her doctorate and becoming a college professor of English and linguistics.

In 1984, Sister Thea faced devastating challenges: both her parents died, and she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Sister Thea vowed to “live until I die” and continued her rigorous schedule of speaking engagements. Even when it became increasingly painful and difficult to travel as the cancer metastasized to her bones, she was undeterred from witnessing and sharing her boundless love for God and the joy of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Donned in her customary African garb, Sister Thea would arrive in a wheel chair with no hair (due to the chemotherapy treatments) but always with her a joyful disposition and pleasant smile. She did not let the deterioration of her body keep her from one unprecedented event, an opportunity to address the U.S. Bishops at their annual June meeting held in 1989 at Seton Hall University in East Orange, NJ. Sister Thea spoke to the bishops as a sister having a “heart to heart” conversation with her brothers.

She explained what it meant to be African American and Catholic. She enlightened the bishops on African American history and spirituality. Sister Thea urged the bishops to continue to evangelize the African American community, to promote inclusivity and full participation of African Americans within Church leadership, and to understand the necessity and value of Catholic schools in the African American community. At the end of her address, she invited the bishops to move together, cross arms and sing with her, “We Shall Overcome.” She seemingly touched the hearts of the bishops as evidenced by their thunderous applause and tears flowing from their eyes.

During her short lifetime (52 years), many people considered her a religious Sister undeniably close to God and who lovingly invited others to encounter the presence of God in their lives. She is acclaimed a “holy woman” in the hearts of those who knew and loved her and continue to seek her intercession for guidance and healing.

Today across the United States there are schools; an education foundation to assist needy students to attend Catholic universities; housing units for the poor and elderly, and a health clinic for the marginalized named in her honor. Books, articles, catechetical resources, visual media productions, a stage play, have been written documenting her exemplary life. Prayer cards, works of art, statues, and stained-glass windows bearing her image all attest to Sister Thea’s profound spiritual impact and example of holiness for the faithful.

The U.S. bishops endorsed the sainthood cause of Sister Thea Bowman on Nov. 14, 2018, during their fall assembly in Baltimore. The granddaughter of slaves, she was the only African American member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, and she transcended racism to leave a lasting mark on U.S. Catholic life in the late 20th century.